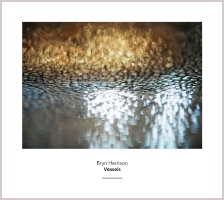

A single, extended work for solo piano, composed by Bryn Harrison, for Philip Thomas

“Bryn Harrison’s music has often, and understandably, been compared with Morton Feldman’s. But while Harrison admires the latter’s immersive quality, his own music has become progressively less harmonic than Feldman’s. Vessels is about ‘the micro-repetition of intervals, the repetition of phrases and the repetition of sections’, Harrison comments. ‘The music [aims to be] perpetually regenerative… constantly opening up, but then [we find] ourselves in the same space’. Citing artist Bridget Riley, he argues that ‘repetition can [highlight] things that might otherwise go by unnoticed’ – though here, repetitions are never exact. Compared to its inspiration, Howard Skempton’s 2007 string quartet Tendrils, this work seems to favour stasis over movement. In contrast to the familiar artistic image of organic inevitability, Vessels seems to unfold according to a law of nature, or mathematical equation. It plays with psychoacoustics, perhaps suggesting the Shepard tone, the aural illusion of constantly rising tones – whatever the acoustic facts, there’s always a sense of rising in one part or the other. Some critics have accused this work of failing to present any listening challenges; of having an almost anaesthetic impact. But this is unfair. Momentum has to be maintained, as it is here by pianist Philip Thomas, who shows immense stamina and concentration over 76 minutes, with a touch of great delicacy. And despite my earlier comments, the irregular, halting rhythms throughout strongly imply a human presence. The result may not be to everyone’s taste, but it’s certainly novel, paradoxical and intriguing.”

Andy Hamilton, International Piano

“This recording represents the intersection of three of England’s most interesting forces in new music—pianist Philip Thomas, composer Bryn Harrison, and Sheffield-based label Another Timbre. Huddersfield resident Thomas has been a leading advocate for experimental music. Earlier in 2013, he brought the shorter version of Vessels on tour with him in Canada alongside other English and Canadian pieces. Here in its full duration, Harrison’s piece is at once hypnotic and demanding of the listener. Thomas’ deft touch and keen ear bring the work’s beauty and unsettling peculiarity to life. Vessels’ suspended, quiet relentlessness might recall Feldman’s late work, but Harrison’s piece is considerably more minimalist and quite without the stylized contours and breaths for which the older composer is known. This economy of material and flatness of perspective, however, are precisely what make Vessels so captivating, as they focus the ear toward the cryptic flow of the piece rather than the singular beauty of each moment. Its surface is very inviting, yet once listeners enter the world of the piece, they’re confronted with an intangible, mysterious process which unfolds for the work’s full duration. It’s the inverse of, say, one of Steve Reich’s process pieces, for whatever is changing throughout the course of Vessels is not readily available, eliciting a disorienting temporal friction between apparent stasis and subtle, constant transformation. Where the trajectories of some minimal works provide lulling stability, Vessels seems to seep in many simultaneous directions, engendering, instead, a heightened awareness of one’s own bewilderment. ”

Nick Storring, Musicworks

“Vessels is the final disc in the new batch of releases on the Another Timbre label, which is concentrating more and more on young minimalist composers. The final disc, and certainly the most radical. Here the composer Bryn Harrison presents a long, fluid piece for piano, played by Philip Thomas. A piece which seems to have no beginning or end, which could last for eternity, and which seems to exist completely outside of time. In his interview on the label’s website, the British composer clearly talks about Feldman (but also of Messiaen, Skempton, Cage, Richard Glover and others). Clearly, because his piece cannot but bring to mind the late works of Feldman. Starting with nine notes taken from a mode of Messiaen’s, Harrison has written a 75 minute composition based on the constant repetition of intervals, phrases and sections. It’s a very long piece with an opaque structure, which moves forwards without a break. The tempo is medium and never varies, the dynamic is also constant, and the pedalling similarly: everything depends on minute rhythmical and harmonic variations. The intervals change slightly, a rhythmic structure subtly shifts, and so on. The scale of nine tones used here appears totally abstract with regard to the piece as a whole. But Harrison works on the tiny details, exploiting countless variations of intervals, intensity and rhythm. Harrison explores the scale concretely, in all its physicality, but in such detail, and at such length that it seems to become abstract. But it isn’t these compositional processes that recall Feldman, it is rather the sense of wandering outside of time which brings this music close to the late works of the American composer. And here we must acknowledge the patience and perseverance of Philip Thomas, who recorded the piece in a single take, with passion and unfailing concentration, and with a sensitivity and precision which sets him apart from so many interpreters. For its entire 75 minutes Vessels never departs from its single-minded and obsessive nature. The nine notes of the scale are explored without harmonic or structural goals; you never know where you are going, nor where you have come from. There is always the feeling that Thomas is playing freely with the scale, in an almost aleatoric way, that he’s playing without thinking of anything, without aim or direction. And it is this absence of purpose which plunges this piece into a very special temporality. A temporality which seems absent; time seems to be stuck around these nine notes, whose variations seem to be inexhaustible, and something to which you could listen for hours on end. A sense of eternity, of dislocated temporality. And this sense draws the listener into a unique auditory experience, one that is rarely found in music: to be outside of time, or at least in another kind of temporality. Unique and very beautiful.”

Julien Heraud, Improv-sphere