Chris Burn – pressings and screenings (2005)

Michael Finnissy – Jazz (1976)

John Cage – Variations II (1961)

Paul Obermayer – Coil (2001)

Mick Beck – Not Just a Load of Balls (2005)

Simon H Fell – Composition No.73: Thirteen New Inventions (2005)

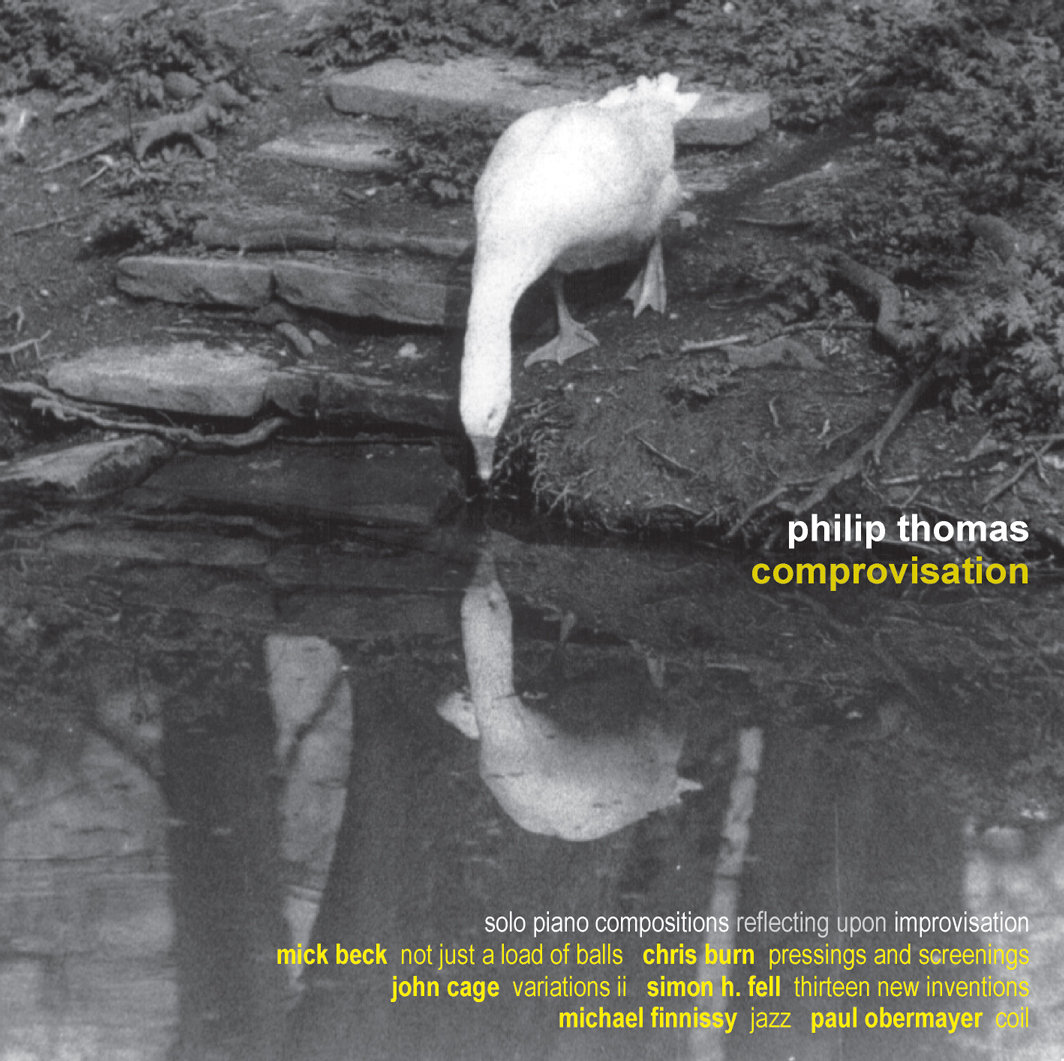

Derived from the concert series of the same name, this recording features five first published recordings (all except Cage) and three piece commissioned and premiered by Philip Thomas (Beck, Burn and Fell)

“The portmanteau title of this incisively played and very clearly recorded sequence reflects Thomas’s dual interest in complex avant-garde music and free improvisation, and in the places where the extremes meet. Finnissy’s Jazz, for instance, is both a spectacular notational extravagance and something close to freewheeling jazz. Paul Obermayer’s coil is a less extreme instance of such complexity, and a most invigorating one, seeming to end with the atonal equivalent of a thumping cadence (but not quite doing so).”

– Paul Driver THE SUNDAY TIMES

“One of the pleasures of writing reviews is that from time to time you come across a totally unknown musical universe that really hits you. Overviewing the catalogue of the Bruce’s Fingers label, it is clear that it is a high quality label of improvised and other contemporary music. The website of the label is very informative, giving lots of background information, through interviews with Fell, etc. Comprovisation is a solo CD by new music pianist Philip Thomas from Sheffield. He performs works from, besides Fell, Paul Obermayer, Chris Burn, Michael Finnissy, John Cage and Mick Beck, featuring music from recent series of concerts of the same name. The works by Beck, Burn and Fell were specially written for Thomas. All the works have in common that it are compositions that play with improvisation in one way or the other. The composition by Fell on this CD is called Thirteen New Inventions and is the result of Fell’s research on Bach’s keyboard repertoire. Some of the parts of this work are indeed close to Bach, in the way that the influence of Bach can be recognized. Other parts however are completely different in nature and dynamic. Thomas feels very much at home in this work and gives a fine and dedicated interpretation of all the compositions on this excellently recorded CD.”

– Dolf Mulder VITAL WEEKLY

“The British new music pianist Philip Thomas specializes in performances of composers like Helmut Lachenmann, Christian Wolff, and Morton Feldman – in other words, music that mixes traditional notation with details of graphic or nonspecific indeterminacy, if not outright improvisation. His album Comprovisation (Bruce’s Fingers) not only includes scores of wildly contrasting nature by classical composers Michael Finnissy (a complexly notated piece of pastoral cascades interrupted by pummeling rhythms titled, perhaps with tongue-in-cheek, “Jazz”) and John Cage (his abstract “Variations II”), but compositions by musicians better known as free improvisers—pianist Chris Burn, multi-reedman Mick Beck, bassist Simon H. Fell, and (if I may coin another description) electronicist Paul Obermayer – which raises several questions. Do free improvisers bring a unique sensibility to a primarily classical format? Do any jazz influences remain audible? Obermayer, for one, is a member of the wildly unpredictable groups Bark! and Furt (the latter an electronic duo with cross-genre composer Richard Barrett), and his “coil” takes great pains to reconfigure a sequence of musical cells in and out of serial (post-Schönberg) procedures. The sharp rhythms and atonal melodies are reminiscent of gestures improvised by Howard Riley, in one sense, or events constructed by Stockhausen in his Klavierstücke for that matter, but there is nevertheless a studied rigidity to the phrasing that suggests this is notated and not spontaneously developed. Chris Burn’s “pressings and screenings,” conversely, alternate dynamically varied chords and clusters with drizzled notes that surreptitiously reveal slivers of Monk’s “Trinkle Tinkle” and “Epistrophy.” Of all these works, Fell’s “Composition No. 73: Thirteen New Inventions” is the most traditional – paradoxically, because he is the musician most accustomed to working with the freest of improvisers as well as the most experienced with modern orchestral maneuvers (as we shall see). His “Inventions” refer to J.S. Bach’s “Two-Part Inventions” for keyboard and, like Dmitri Shostakovich’s “Preludes and Fugues” op. 87, they adapt Bach’s contrapuntal form to his own melodic language. These are playful miniatures, with propulsive rhythms, hammered attacks, grand Lisztian gestures, classical allusions, and not much apparent jazz, as if that matters.”

– Art Lange POINT OF DEPARTURE (on-line journal)

“CD solo debut for avant garde king: adventurous pianist Philip Thomas continues to enjoy himself exploring new pianistic boundaries and has just released his first solo CD….. Given the who’s who of composers in his huge repertoire, few of them conventional, he is one of the UK’s leading avant garde, a term rarely used now – it’s either new, progressive or experimental music, pianists. A lot of Philip’s success in performing much of the material he does is down to his utter belief in it and enthusiasm in exploring it, allied to rock-solid piano-playing technique. All this somehow manages to transmit itself on his new solo CD, Comprovisation (broadly, a term for notated music with elements of improvisation), the title of his last Sheffield concerts in 2005. Pieces by Paul Obermayer, Chris Burn and John Cage – Variations II, an exercise in timing – can be appreciated on a dispassionate cerebral level. For those wanting something a little more tangible, the standout pieces are Michael Finnissy’s densely virtuosic Jazz and Simon H. Fell’s Thirteen New Inventions, rather clever and skilful homage to Bach, commissioned and premiered by Philip at Persistence Works in December 2002.”

– Bernard Lee SHEFFIELD TELEGRAPH

“At first it is frustrating that, despite telling us that these pieces are a mixture of the fully notated and the partly improvised, Philip Thomas doesn’t expand his sleevenotes to tell us which are which. But it emerges on listening that this is partly the point. The very word, comprovisation, no longer acknowledges a division between the two. From compositions by improvisers like Mick Beck and Chris Burn, to compositions informed by improvisation, like Finnissy’s Jazz, to compositions that vehemently resist improvisation against all expectations, like Cage’s Variations II, Thomas has found several interesting points between the two poles. Paul Obermayer, best known as a laptop improviser with FURT and Bark!, was a good place to start the debate with his (presumably intricately notated) coil. Fans of Obermayer’s work with Richard Barrett will know what to expect here: music compressed like raw carbon into diamond shards. This makes a gritty start to the CD to which it doesn’t really return. In the next piece Burn brings a more obviously improvisatory feel through the frequent returns to collections of related gestures, which feel jazzy in their loose rhythms and the wide, swinging movements they demand of the pianist; this sort of playing is more characteristic of the rest of the disc. The Finnissy is perhaps more intellectually stimulated – it jazz-es rather than is jazz-y – but it still retains that impression of delicate flexibility that characterises much of his piano music. Its wide registral spacing nods towards Jelly Roll and boogie woogie; and its sudden shifts of character – as though structured around 16-bar verses – recall a wider jazz idiom. Mick Beck calls for balls of various weights and sizes, which are bounced around the inside of the piano and occasionally out onto the studio floor, and Simon Fell takes a final, different approach to the issue of accident versus control, basing his Inventions on improvisations on Bach, and coming up with the some of the most emotionally involving music of this CD. Although the musical quality is sometimes uneven, Thomas’s concept in this recording – and the series of concerts from which it sprang – remains as valid as ever, and continues to engage many of the most interesting voices in British music. Comprovising without compromise.”

– Tim Rutherford-Johnson NEW NOTES