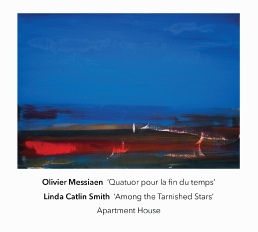

Linda Catlin Smith Among the Tarnished Stars (1998)

Olivier Messiaen Quatuor pour la fin du temps (1941)

Apartment House: Anton Lukoszevieze (piano), Mira Benjamin (violin)

Heather Roche (clarinet) & Philip Thomas (piano)

‘Four members of Apartment House bring their cumulative insight and expertise as interpreters of experimental music to a performance that respects the intrinsic poise as well as the bold contrasts and occasional flamboyance of Messiaen’s score. By avoiding superfluous expressive artifice they allow this music to breathe. It takes on fresh life, and Smith’s Among The Tarnished Stars works beautifully as a prelude.’

Julian Cowley, The Wire

“And have you considered timbre,” interjected the senior scholar, aware of her advantage. The junior scholar, knowing his stake in the game but obviously flustered, floundered for a retort. “Well, I haven’t … I don’t see how I could … I mean it would …” “You haven’t? OK, you just go ahead and keep doing what everybody else does.” The conference room crackled with energy, as often happens in those moments of intergenerational confrontation, but she had made her point. There is a sense in which timbre has been the black sheep of analysis’ rapidly growing family, partly because we’re still attempting to codify a descriptive language for it. Scholarship at large has chosen to ignore it, but it is certainly among the most important elements of sound-art since 1900. I certainly do not mean to imply that earlier music lacked it, but its relevance has been explicit since Arnold Schoenberg and Charles Ives threw down timbral gauntlets around 1910. Justifying the name of the label housing it, this disc’s music and performers thrive on sound, its multivalent colors and their structural primacy, supported by a recording second to none.

There is no better ensemble to make the point than Apartmenthouse and no better composer to offer a worthy vehicle than Linda Catlin Smith, whose 1998 piece “Among the Tarnished Stars” provides the album’s point of entry. This reading is about six minutes slower than the only other I’ve heard, from the composer’s site, and while it is just like this ensemble to radicalize elements of tempo and dynamics, timbre is paramount. Every shade and color pianist Philip Thomas brings to bear on his opening ascending figures is captured with clarity and vivid contrast, enough so that Mira Benjamin’s violin, Anton Lukoszevieze’s cello and Heather Roche’s clarinet conjure shades of mellow Duke Ellington orchestrations upon entry. The nearly half-hour piece is about octave drone, disparate voicings, quasi-canon and dynamic contrast. Ensemble seems to grow and shrink while gestures emerge as, intriguingly, sheer beauty and sonic largess render actual group size irrelevant. String figures throb, swell and retreat, the tone world supported by seemingly infinite and ever-changing colors that slide in and out of focus with consummate grace.

The longer work on offer here provides some evidence, as several fantasy writers postulate, that the future can control the past, but Catlin Smith’s piece needs to be heard first for the desired effect. It’s an astonishing programming decision, and it’s invigorating to hear a piece of music rendered in a way that simultaneously defies and pays multivalent homage to history. To cite a lack of sentimentality in Ensemble Apartmenthouse’s reading of Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time — I’ll be using English translations in this review — would be to belittle an accomplished and often maverick performance. The eight-movement suite, composed in 1941 and scored for identical forces to the Catlin Smith work, is likely Messiaen’s most recorded composition, and the competition is fierce. Apartmenthouse sidesteps such concerns. It may be easiest, when discussing an approach as radical as this one, to let a moment serve to illustrate the whole, such as the middle section of “Vocalise for the Angel who Announces the End of Time.” The most obvious departure concerns vibrato, which is almost entirely lacking, in this movement and throughout the disc. Its absence is most startling in “Vocalise”’s middle section, which, according to the composer’s program note, is meant to represent “the impalpable harmonies of Heaven.” Messiaen speculates on eternity’s sound quite often, creating gorgeously slow and often hushed ecstatically long lines of rapturous quasi-repetition.

Never have I heard any pair of string players execute the violin and cello parts as do Benjamin and Lukoszevieze. They achieve a unity of timbre and glissando that sometimes makes their combined instruments sound like Messiaen’s beloved ondes martenot, a keyboard-driven relation to the theramin, so that preechos of the angelic music scene in Messiaen’s St. Francis opera are unavoidable. It is almost as if “Tarnished Stars” informs the quartet in hindsight, so closely does it resemble that vision of eternity and all of the more reflective passages of the quartet, such as the similarly suspended middle section of “Dance of Fury, for the Seven Trumpets.” Indeed, the entire movement, all octaves of varied intensity, takes on the calm of its middle section to startling effect. Thomas’ pianism exudes Debussey-like calm rather than the standard wrath, so different from every other conception I’ve experienced.

The sense of an intergenerational dialogue, on many levels, becomes more palpable with each hearing. Again, a moment speaks volumes as Roache’s take on the solo tour de force “Abyss of the Birds” reconjures the theramin, so rich in overtone but crystalline is the timbre of her opening tones; she places special emphasis on the first five notes, which Messiaenites will recognize as a motive so often used by the composer throughout his long career. The disc is a unity in diversity, a fact which would doubtless have pleased Messiaen no end, and this triumph of recording and performance should be heard by anyone with the slightest interest in the piece or in its musical implications.’

Marc Medwin, Dusted

‘I came to Messiaen fairly late in my listening career. For a long time, his was a name, not much more. Somewhere in the early 80s, I picked up the Philips recording of the Quartet, probably due to the presence of Vera Beths on violin, whose name I knew from her involvement with a number of Willem Breuker projects (I was way into Breuker then; the Doré engraving on the cover didn’t hurt, I’m sure). The name of the pianist on the date, Reinbert de Leeuw, meant nothing to me at the time! It had a strong effect on me, both the historical facts of its creation and, especially, the two louanges. Still, I filed it away and managed to, more or less, forget about it. Some years later, when Zorn included a cover of the ‘Louange à l’Eternité de Jésus’, I recall it took me a few moments to place the work; odd. In any case since then, I’ve listened to many a reading of it and more Messiaen besides, though I’m still far from any kind of thorough investigation. I listened to a few more in recent weeks and bought an old copy of the Erato vinyl, an early 60s recording with Huguette Fernandez, Guy Deplus, Jacques Neilz and Marie-Madeleine Petit, but apart from some obvious differences in approach it’s beyond my ears and my available time to sit and do a proper comparison, not that it’s necessary. I discussed the work a bit with Keith Rowe and he pointed me to this very interesting critical exchange on BBC Sounds, which readers might enjoy.

But first things first. There are two works presented on this fine disc, each performed by members of Apartment House (Mira Benjamin, violin; Anton Lukoszevieze, cello; Heather Roche, clarinet; Philip Thomas, piano). Though it’s not mentioned anywhere I could find, including the text on the Another Timbre site, I take it for granted that, not only by virtue if the relatively unusual instrumentation but amore importantly considering its overall sound, that Linda Catlin Smith had the Messiaen at least partially in mind when she composed the extremely beautiful piece, ‘Among the Tarnished Stars’ (1998). The initial section’s poignancy seems to be an indirect allusion to the louanges, though perhaps a bit more grounded, less trusting in the likelihood of spiritual salvation. It shifts subtly throughout its 28 minutes, maintaining a somber quality. The piano hits chords evoking the striking of dull metal as the clarinet intones a sorrowful hymn. Gentle glimmers appear via occasional upward lines, the strings and clarinet adopting a kind of breathing, sighing pattern in the still air. Another deep, evocative piece from Smith; I’m very happy this label has done yeoman’s work in getting her music out into circulation.

As said above, comparisons with other recordings are beyond my pay grade, though this quartet approaches the work with a certain kind of rigor and lack of any tinge of sentimentality, partly expressed by the relative lack of vibrato. The line in the ‘Vocalise’ is taken a bit more slowly than I’m used to, less stridently. Lukoszevieze mentions thinking of the cello part in the first louange as a kind of blues and that comes through to these ears. Thomas does something on the last movement, a slight dampening of the second of the doubled chords played (via pedal manipulation, I take it) as a kind of “ghost chord”, a faint echo, or maybe I’m simply imputing that due to the extremely fine level of touch employed by Thomas. Whatever the case, I find this effect to be very moving and beautiful. At the end of things, I can only say that, for me, this reading of the Quartet fits in quite comfortably with past favorites, holds its own very well and, in fact, is better recorded than many, giving it a bit of an edge on that front. It’s entirely worth hearing of you’re a fan of the piece–mandatory, even.’

Brian Olewnick, Just Outside

‘Who would have thought that Messiaen needed rescuing? Yet all this time, in full view, his reputation has been in peril. Despite his secure position as one of the great figures of twentieth century music, he is often met with the Wrong Sort of apprehension – not for being “too modern” but for being too ornate and overbearing, loaded down with symbolism that he elaborates upon to an extent that tests the audience’s Sitzfleisch. He was teacher to a generation of avant-garde luminaries who waved off his radical techniques and gently dismissed him with the contempt bred by familiarity. Messiaen is now a double image that cannot be reconciled; he has been embraced by an audience at the expense of his modernity, while the more progressively minded continue to regard his modernity askance. We are only permitted to see him in part at any time. Advocating for him as an innovator is made to seem like a revisionist act.

It seems like a bold move for a new recording of Quatuor pour la fin du temps to be released by Another Timbre, a record label that’s made its name for working a rich seam of contemporary music while seldom straying beyond a range that extends from, say, John Tilbury to Wandelweiser. For those already familiar with this classic, this interpretation should come as a discreet but satisfying revelation. Rather than trying to reinterpret or (God forbid) ‘reimagine’ Messiaen, the musicians make a clear-eyed attempt to see his work plain. As with many twentieth century composers, first recordings of Messiaen have a rawness that comes with the strangeness of the new musical idiom and the need to emphasise the new, alien quality. A modern group taking this stark, ‘just the notes’ approach would be boring, uninflected and perversely colourless. For Another Timbre, the musicians are Heather Roche on clarinet, violinist Mira Benjamin, cellist Anton Lukoszevieze, and Philip Thomas on piano. I’m sure I’ve discuss solo performances and recordings by all four musicians many times before. They each excel at new and contemporary music, through both technical achievement and interpretive nous. They approach the Quatuor as a contemporary work, combining flowing virtuosity with an appreciation for grit, never taking the composer’s craft for granted.

This performance-based approach produces rhythms and phrasing that are more deliberate (not necessarily slower) than other versions I remember. It stays true to the complex emotional experience of hearing the sute of eight movements while giving clarity to certain points. The opening “Liturgie de Cristal” emphasises is strangeness through its abruptness, hammered home by the sudden contrasts in the following Vocalise. Messiaen comes across as prescient of current musical trends here, particularly in the glacially slow clarinet solo “Abîme des oiseaux”, played by Roche with a tone that’s both pensive and unyielding, and “Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes”. The latter, played by all four in unison, is the most arresting version I’ve heard: the lock-step precision produces a unique timbre and repeated phrases take on an urgency I haven’t heard before. Messiaen has the capacity to shock.

The Quatuor is paired with a piece for the same four instruments by Linda Catlin Smith, whose work has been presented on Another Timbre a couple of times before. Among the Tarnished Stars is an older work, from the late Nineties, which may be why it bears some more overt resemblances to other composers. In particular, it recalls late Feldman at his most extroverted, i.e. short fragments of lyricism in a tone that’s more wistful than claustrophobic. Piano plays against the clarinet and strings like a muted concerto. A less overtly dramatic work than the Messiaen, it still provides plenty of contrasts and incidents while still feeling compact at half an hour length. Heard alone, it could provide a fitting epilogue to the Quatuor, but in fact precedes it on the disc. It seems an unusual choice to have the later work first, but in this way it sets a new context in which Messiaen may be heard. Smith’s music is clearly a work of the present time without ornamenting itself with any overt signifiers of end-of-century fashions, whether cultural, social or technological. Messiaen’s connections with contemporary music may now be more closely observed.’

Ben Harper, Boring Like A Drill